Through much of the book, Joe is synonymous with anger, angst,

confusion, and violence. Not only does he not find peace, but he does not even

attempt to obtain it, instead seeking conflict wherever he can get it. Though

he was a victim of poor circumstances, it is unfair to say that Joe was a man who

could never catch a break. One merely needs to look at the female figures in

his life, particularly the maternal Mrs. McEachern and the woman he could have loved, Ms. Burden, to find that love and

compassion was only a compromise away. Joe merely needed to give in to their

empathy and he would have found love, and yet he refuses to do so. Why he does

this is one of the major questions Faulkner poses in the novel. One could say Joe is simply

hell bent on a heartache, and yet that would be a reductive answer that barely

scrapes the surface of his psychological world. What really seems to be the

motive behind Joe’s defeatism is an intense inner need for dominion. He can

only obtain this through constant strife with others and never allowing himself

to succumb to kindness, since that would put him in a position where he relied

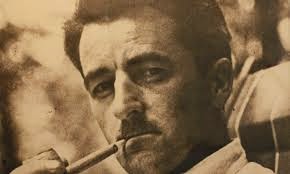

on others. There are already so many actors lined up in my mind who could play this character.

Through much of the book, Joe is synonymous with anger, angst,

confusion, and violence. Not only does he not find peace, but he does not even

attempt to obtain it, instead seeking conflict wherever he can get it. Though

he was a victim of poor circumstances, it is unfair to say that Joe was a man who

could never catch a break. One merely needs to look at the female figures in

his life, particularly the maternal Mrs. McEachern and the woman he could have loved, Ms. Burden, to find that love and

compassion was only a compromise away. Joe merely needed to give in to their

empathy and he would have found love, and yet he refuses to do so. Why he does

this is one of the major questions Faulkner poses in the novel. One could say Joe is simply

hell bent on a heartache, and yet that would be a reductive answer that barely

scrapes the surface of his psychological world. What really seems to be the

motive behind Joe’s defeatism is an intense inner need for dominion. He can

only obtain this through constant strife with others and never allowing himself

to succumb to kindness, since that would put him in a position where he relied

on others. There are already so many actors lined up in my mind who could play this character.

I just read the novel for the first time last month, and I'd be lying to myself if I didn't include it in my personal cannon of great literature. I would also be lying to myself if I said it couldn't make a great movie. This is one of the few Faulkner novels that really is filmable (with all due respect to James Franco's As I Lay Dying, which was a fine attempt, but less of a movie than a project, an homage to the difficulty and strangeness of Faulkner through a different medium). The narrative and characters, while enormously complex, are not out of reach. Faulkner spells a lot out for the reader and steers clear of the stream of consciousness that makes so much of his other great novels so baffling. It would be a challenge, but anyone with a true passion for the characters Faulkner creates (not just Joe Christmas, but the pregnant Lena Grove, her runaway coward boyfriend, the reverend Hightower, who is plagued by the Confederate cavalry, and Byron Bunch, the only good person in the novel) could potentially at least put together a workable script. Dreyer may not have gotten away with some of the more gruesome and seedy elements of the novel, and yet the concerns of his own films' characters suggest he would have been able to develop Faulkner's characters with precision and understanding. In an article for the Criterion Collection, Jonathan Rosenbaum writes:

For all its radical differences in period (1906), milieu (Copenhagen), and class (upper) from Light in August, Gertrud is no less preoccupied with questions about existential identity—for the implacable title heroine (who, like Lena Grove, lives in a continuous present and never changes) and for the various men who pursue or abandon her (preoccupied with the past and their own careers). There isn’t much room for comedy here (as we get in the final chapter of Light in August), certainly not in the tragic failure of the men to live up to Gertrud’s ideal of total love and commitment, or in Gertrud’s own tragic inability or refusal to compromise her ideals. But the tension between narrative and nonnarrative forms of presence, between stillness and instability, is remarkably similar in the two. And the piercing, exquisitely “overlit” flashbacks and epilogue of Gertrud evoke some of the charged luminosity of Faulkner’s world.

No comments:

Post a Comment