But besides that, it's how Petzold goes about bringing this idea to life that warrants the most focus. Two of the biggest aspects of why such a seemingly implausible project comes across so effortlessly and flawlessly is that it has Nina Hoss (who, like Cate Blanchett, is a master when it comes to communicating emotions through lip movement) as its star and because as a director, Petzold has some brilliant strategies that combine perfectly timed cuts, lighting, great dialogue, and the nuanced performance of his leading lady to make the film work dramatically, emotionally, and efficiently.

Here's an example of this: Hoss plays a Holocaust survivor named Nelly who returns to post-war Germany with a reconstructed face due to the horrors she suffered in the concentration camps. She's staying in an apartment with her friend Lene, who at this point is her only acquaintance who knows that she's alive. Nelly, calling herself Esther, goes out into the city at night to find her husband, Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld), who now goes by Johannes and works at a night club called Phoenix. When she encounters him, Johannes sees a vague semblance of his assumed-to-be dead wife, and quickly concocts a plan in which Esther will pretend to be Nelly so that she can claim her inheritance, after which the two will split the money and part ways (Johannes can't claim it himself because he has no actual proof that Nelly died).

The viewer is a little shocked by this plan, which must pale in comparison to what Nelly is feeling. But she goes along with it, partly because it allows her to simply be around her husband again, and also because Johannes' means to an end is her end in itself. She simply wants to be her old self again, and getting there is enough to overlook, or simply ignore, the true nature of Johannes' scheme.

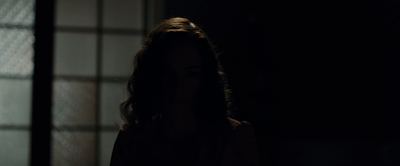

With the groundwork laid for the movie's plot, we get a scene between Nelly and Lene after the former has returned from her encounter with Johannes. First we see her silhouette through the glass door that leads to Lene's room, but because the room is dark, when she enters we still can only see her shape as she gently wakes Lene. Because there's light coming in from the door, we can make out Lene's features, but with her back to it Nelly remains cloaked in darkness and tells Lene to keep the light off when she reaches for the switch. "You saw him," Lene says, which Nelly confirms. She asks what happened, but all we get is a shot of Nelly dropping her head down, and then the scene ends.

It's a brilliant use of light, or lack thereof, because it serves as a reflection of Nelly's inner world. No, it's not that it's a metaphor for a darkness or bleakness inside her, but that now that she's come in contact with Johannes, with her old life, her new one, her new face, becomes all the more unbearable. And yet she still has to wake Lene up because this is exciting for her: it's the beginning of what she hopes will be a revival of something lost, even if the getting there is a bit more wild than she'd hoped. It's disappointing that this revival is built around such a sneaky plan, which is why she simply hangs her head when Lene asks her about it, but it's also the start of a rebuilding process that she desperately needs. While Lene has plans for them to go to Palestine to start a new life, Nelly is bent on regaining her old life, and if she can become a good enough version of her old self, Johannes may realize that it really is her.

Jump ahead much later in the film, when the plan for Nelly to emerge as herself is nearly intact, and Petzold returns to the same room at night, with the same image of Nelly by Lene's bed in the darkness. She's more vocal this time around, explaining that Johannes was the reason she was able to survive the camp: "I only thought about how I'd come back to him," she explains, but when she did and he didn't recognize her, she was "dead again." But, she continues, her hushed voice filled with an almost thrilling sense of hope, "now he's made me back into Nelly again."

It's here that Lene leans over and turns on the bedside lamp, and we see Nelly, with a red dress and lipstick and styled hair. Of course, as we've been following her transformation we've already seen her with this look, but it's still a revelation, first because she's showing someone besides Johannes that her old self has been renewed, and second because she herself is finally acknowledging it.

When we see her with the light on, the image echoes the shot from Vertigo when Kim Novak emerges from the bathroom reformed into the image of Madeleine (the parallels between Phoenix and Vertigo are so extensive that it would take a separate essay to really dig into them, so I'll just mention that one). And yet while she's smiling as we see her in the light, she immediately drops her lips slightly, as if being seen by Lene dispels the magic of the transformation and only suggests the artifice of the entire situation. Which leads to one of the movie's great lines--maybe even one of the great lines ever--as Nelly says, "When he speaks of her...I'm really jealous...of me!" The line demonstrates just how distanced Esther feels from Nelly, and further proposes an idea about her feelings that the movie had yet to bring up. That Nelly feels jealousy over her former self is dangerous because it suggests irrational thought, behavior based on emotion rather than reason. Of course, we've surmised at this point that Nelly is mainly acting out of feeling the entire time, but that that feeling is one of jealousy for her former self gives us a concrete understanding of why she's going along with Johannes' plan. Yes, she wants him back, but it takes a feeling as strong as jealousy to give her the conviction to get rid of Esther and become Nelly again. It's this more than love, I believe, that drives her.

With these two brief parallel scenes Petzold gives us so much information with so little. Basically just a few great lines, a lovely curve of the mouth from Hoss, and the movement from darkness into light. And that's how the movie as a whole works, why it's able to accomplish so much with such a short running time.

No comments:

Post a Comment